Costs, Benefits and Projecting Project Payback

I renewed my subscription to Consumer Reports last month. I don’t buy anything of value without referencing Consumer Reports and two or three other review sources. For instance, I just bought a new lawn tractor. I researched the options for weeks before finally purchasing one. It takes about 1½ hours to cut my lawn with a traditional push mower. I figured a riding mower would cut my mowing time significantly. So my cost-to-benefit ratio was based on money spent now divided by the total number of hours reduced over X years. A no brainer, right?

Well, after cutting my lawn a few times, I’m back to using my old self-propelled mower. Why? I like the results better, and I think it cuts the grass much better. My new rider cost over $3,000. My trusty old mower cost me $279 three years go. Which was the better deal?

A cost-benefit analysis can help maintenance and engineering managers determine how well or poorly a planned action will turn out. It helps determine if it’s a sound investment or decision.

I’m not sure if I did a good enough analysis, but managers are faced with the similar situations face much higher risk and consequences if they don’t perform the analysis correctly. The process involves comparing the total expected cost of each option against the total expected benefits to see whether the benefits outweigh the costs and, if so, by how much.

Managers should follow some general rules in conducting a cost-benefit analysis:

- Calculate costs and benefits for two to five years, starting from the start date of the project.

- Be careful in deciding when to start capturing benefits and how long those benefits will pay back. Only calculate benefits that are realized, and do not extend beyond the planned period.

- Be sure benefits are measurable. This means examining the difference between what would have occurred without the project and the post-project value.

- Do not double- or triple-dip the financial benefits. Some overlap and diminishing returns will occur over the term of the project and beyond.

- Always have someone double-check your numbers. It’s advisable to have the finance department develop and agree to the financial benefits.

- Document assumptions so everyone is clear about the way you calculated the numbers.

Cost considerations

Start the process by making a list of all monetary costs that will be incurred upon implementation and throughout the life of the project. These include: start-up fees, including those for project teams and consultants; systems development; and implementation, training, materials, productivity lost, and relocation, among others.

Then assign monetary values to the identified monetary and non-monetary costs. To ensure consistency across the life of the project, state the monetary values in present value terms (NPV). Add all anticipated costs to get a total costs value.

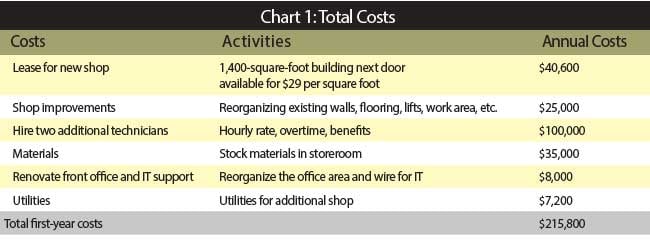

Consider this example: An auto collision shop has been in business for just over two years, and business is exceeding projections. Two technicians work full-time, and the owner is considering increasing capacity to meet demand. This move would involve leasing more space and hiring two more technicians.

Here are several assumptions related to the example. The owner has more work than he can handle and, to keep up, is using another shop, which charges $75 an hour. The owner outsources an average of 100 hours of work each month. The owner estimates the increased capacity will increase revenue by 50 percent. Per-person production will increase by 10 percent with more working space. The analysis horizon is one year, meaning the owner expects benefits to accrue within the year. See Chart 1 for project costs.

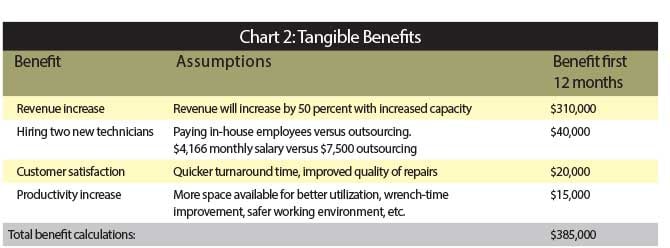

Measuring the benefits from your project is critical and will be essential for success. Most managers fail to properly quantify benefits in terms of financial savings or revenue generation.

Make a list of all monetary benefits the organization will experience upon the project’s implementation and thereafter. Key areas that managers should address are: operational savings and reductions; improved customer and employee satisfaction; increased revenue; an increase in capacity and quality; and health, safety and environmental improvements. See Chart 2 for the project’s anticipated benefits.

The shop owner calculates the return on investment (ROI) will be as follows:

$215,800 / $385,000 = 0.56, or about 6 months

In our example, based on the raw numbers and an assumption, moving forward with leasing additional space is prudent. Of course, the financial benefits are best-guess estimates. Actual costs will determine true returns.

When performing cost-benefit analysis, managers need to keep several things in mind. A cost-benefit analysis is a relatively straightforward tool for deciding whether to pursue a project. To get a rough cut estimate of the ROI, list all the anticipated costs associated with the project including assumptions. Then estimate the benefits it will generate. Finally, where benefits are received over time, work out the time it will take for the benefits to repay the costs.

You might decide to include intangible benefits in the cost-benefit analysis. You might have to estimate a value for these items, so this inevitably brings more conjecture into the analysis. More sophisticated programs and tools can be used for more complicated projects, but a simple cost-benefit analysis can save a great deal of time, energy, and potentially money in the long run.

Topics: facilitiesnet, Article, Leadership

Posted by

Nexus Global

Recognized globally, across various industries, for delivering sustainable solutions that optimize both the organization’s assets and processes to yield a ROI of 10:1 or greater. Nexus Global Business Solutions, Inc. has been a worldwide leader in asset performance management and maintenance consulting, coaching and training for 15+ years.